Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America's dirty secret

What happens to your plastic after you drop it in a recycling bin?

According to promotional materials from America’s plastics industry, it is whisked off to a factory where it is seamlessly transformed into something new.

This is not the experience of Nguyễn Thị Hồng Thắm, a 60-year-old Vietnamese mother of seven, living amid piles of grimy American plastic on the outskirts of Hanoi. Outside her home, the sun beats down on a Cheetos bag; aisle markers from a Walmart store; and a plastic bag from ShopRite, a chain of supermarkets in New Jersey, bearing a message urging people to recycle it.

Tham is paid the equivalent of $6.50 a day to strip off the non-recyclable elements and sort what remains: translucent plastic in one pile, opaque in another.

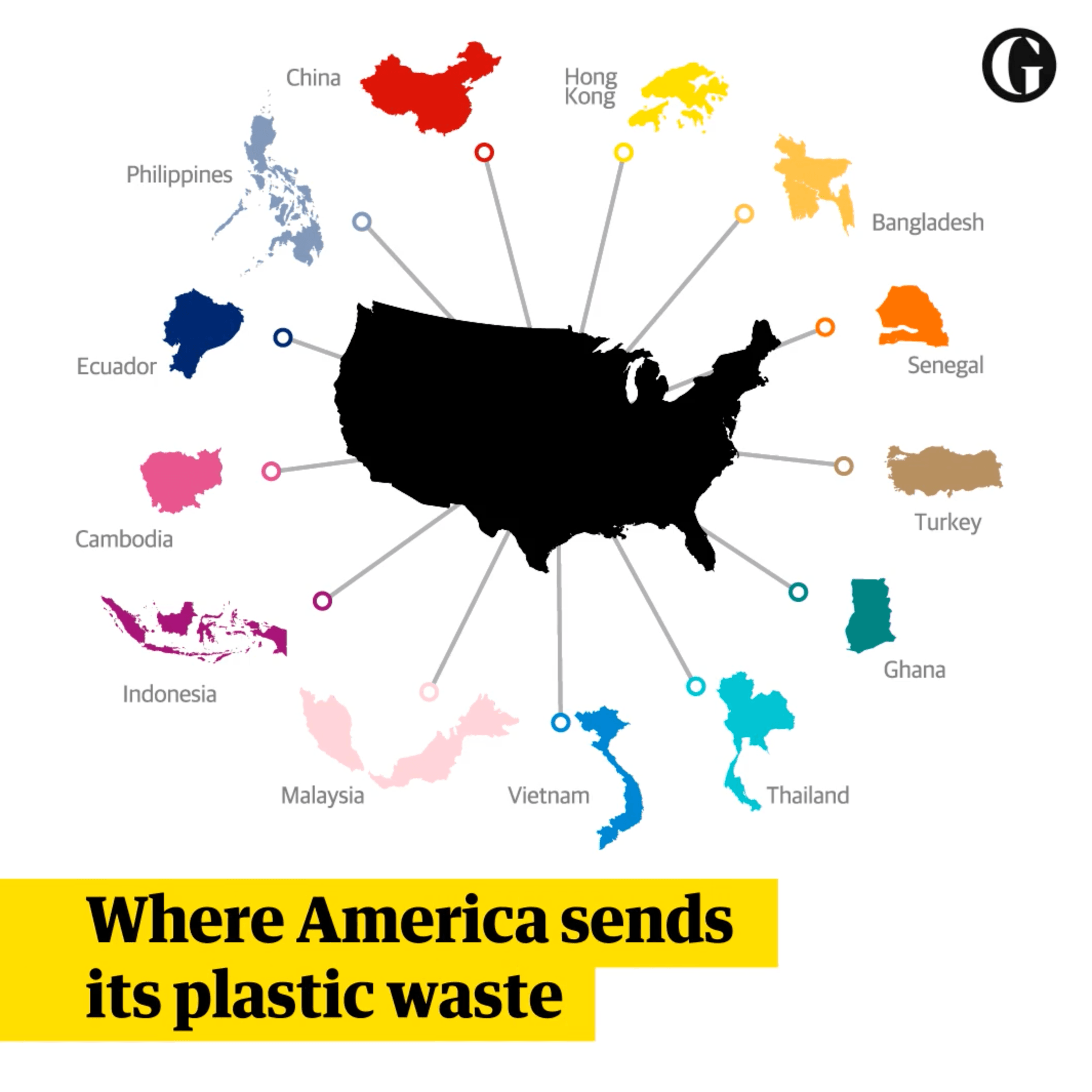

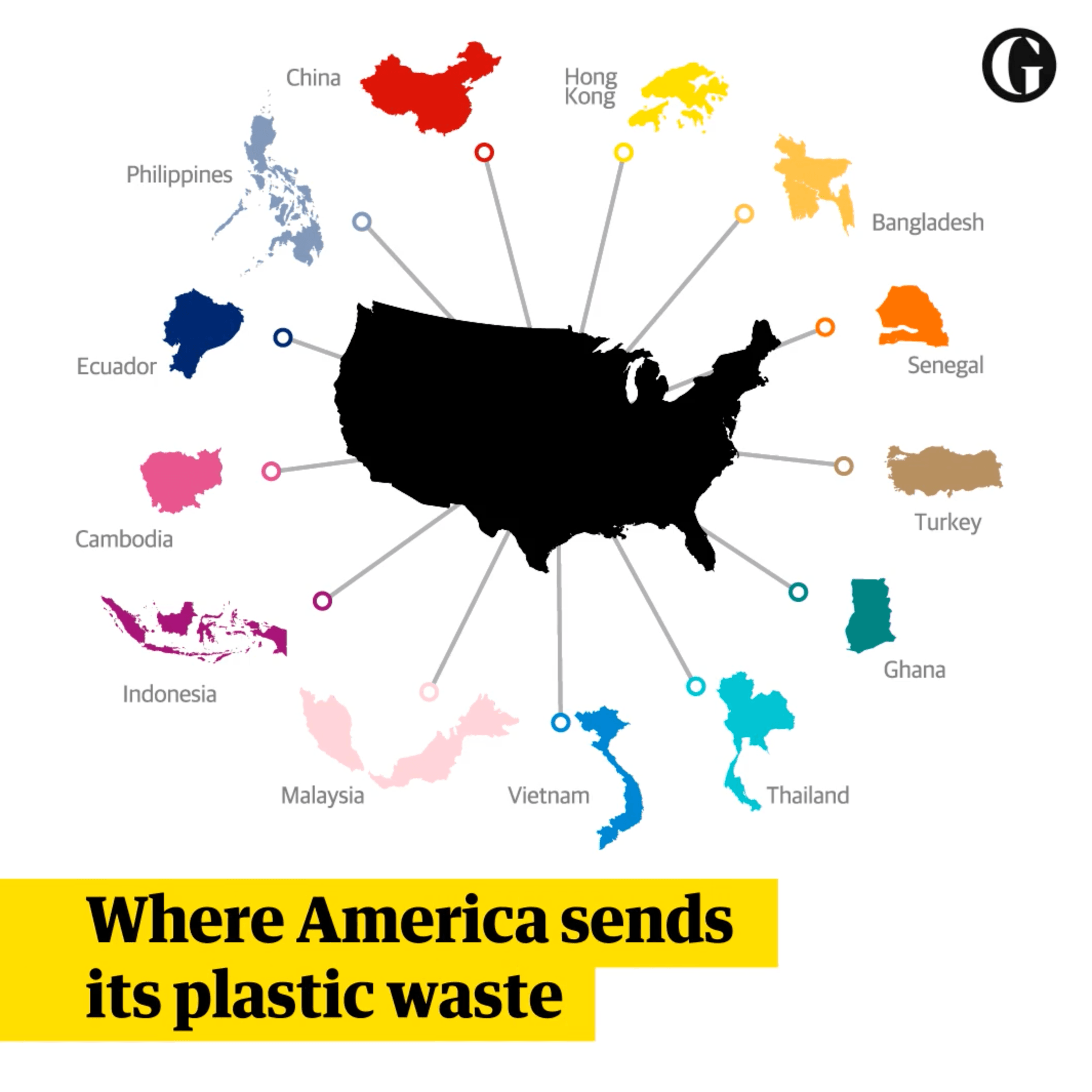

A Guardian investigation has found that hundreds of thousands of tons of US plastic are being shipped every year to poorly regulated developing countries around the globe for the dirty, labor-intensive process of recycling. The consequences for public health and the environment are grim.

A team of Guardian reporters in 11 countries has found:

- Last year, the equivalent of 68,000 shipping containers of American plastic recycling were exported from the US to developing countries that mismanage more than 70% of their own plastic waste.

- The newest hotspots for handling US plastic recycling are some of the world’s poorest countries, including Bangladesh, Laos, Ethiopia and Senegal, offering cheap labor and limited environmental regulation.

- In some places, like Turkey, a surge in foreign waste shipments is disrupting efforts to handle locally generated plastics.

- With these nations overwhelmed, thousands of tons of waste plastic are stranded at home in the US, as we reveal in our story later this week.

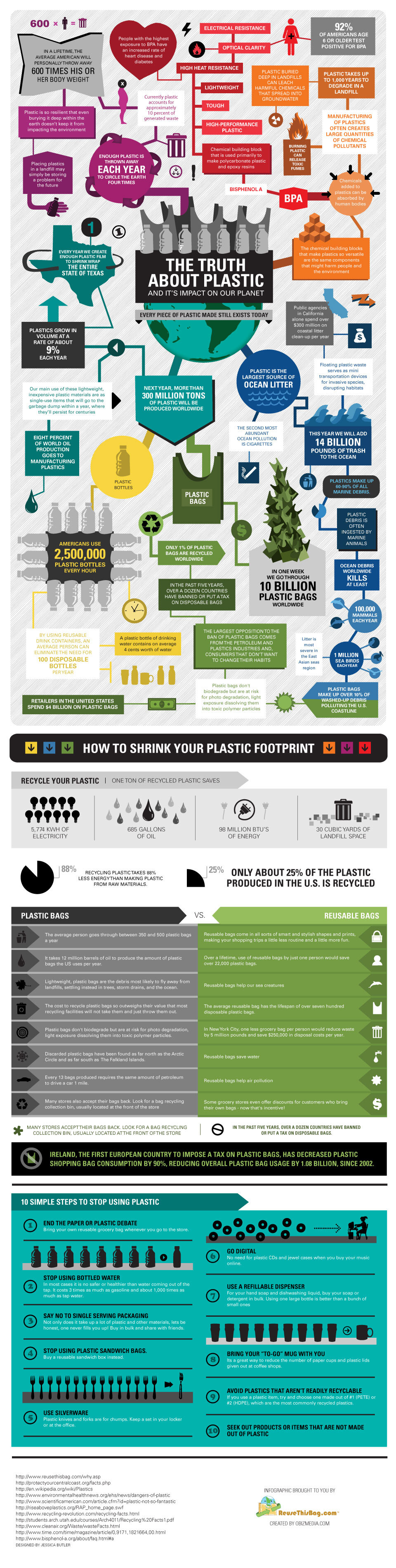

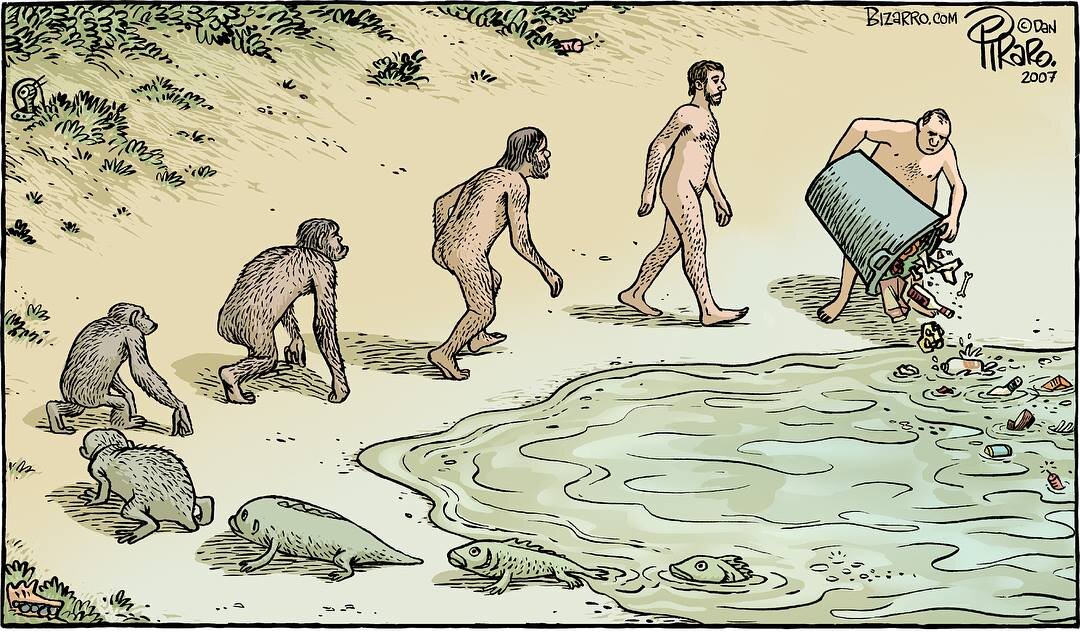

These failures in the recycling system are adding to a growing sense of crisis around plastic, a wonder material that has enabled everything from toothbrushes to space helmets but is now found in enormous quantities in the oceans and has even been detected in the human digestive system.

Reflecting grave concerns around plastic waste, last month, 187 countries signed a treaty giving nations the power to block the import of contaminated or hard-to-recycle plastic trash. A few countries did not sign. One was the US.

A new Guardian series, United States of Plastic, will scrutinize the plastic crisis engulfing America and the world, publishing several more stories this week and continuing for the rest of 2019.

“People don’t know what’s happening to their trash,” said Andrew Spicer, who teaches corporate social responsibility at the University of South Carolina and sits on his state’s recycling advisory board. “They think they’re saving the world. But the international recycling business sees it as a way of making money. There have been no global regulations – just a long, dirty market that allows some companies to take advantage of a world without rules.”

Since the China ban, America’s plastic waste has become a global hot potato, ping-ponging from country to country. The Guardian’s analysis of shipping records and US Census Bureau export data has found that America is still shipping more than 1m tons a year of its plastic waste overseas, much of it to places that are already virtually drowning in it.

A red flag to researchers is that many of these countries ranked very poorly on metrics of how well they handle their own plastic waste. A study led by the University of Georgia researcher Jenna Jambeck found that Malaysia, the biggest recipient of US plastic recycling since the China ban, mismanaged 55% of its own plastic waste, meaning it was dumped or inadequately disposed of at sites such as open landfills. Indonesia and Vietnam improperly managed 81% and 86%, respectively.

“We are trying so desperately to get rid of this stuff that we are looking for new frontiers,” said Jan Dell, an independent engineer, whose organization The Last Beach Cleanup works with investors and environmental groups to reduce plastic pollution. “The path of least resistance is to put it on a ship and send it somewhere else – and the ships are going further and further to find some place to put it,” she said.

Take Vietnam. Minh Khai, a village on a river delta near Hanoi, is the center of a waste management cottage industry. Rubbish from across the world, inscribed in languages from Arabic to French, lines almost every street in this community of about 1,000 households. Workers in makeshift workshops churn out recycled pellets amid toxic fumes and foul stench from the truckloads of scrap that are transported there every day. Even Minh Khai’s welcome arch, adorned with bright red flags, is flanked by plastic waste on both sides.

In 2018, the US sent 83,000 tons of plastic recycling to Vietnam. On the ground, America’s footprint is clear: a bag of York Peppermint Patties from Hershey, with US labeling, and an empty bag from a chemical coatings manufacturer in Ohio.

“We’re really scared of the plastic fumes, and we don’t dare to drink the water from underground here,” said Nguyễn Thị Hồng Thắm, the plastic sorter, wearing thick gloves, a face mask and a traditional Vietnamese conical hat to protect herself from the sun. “We don’t have money so we don’t have any choice but to work here.”

While the exact health effects of workers’ exposure to plastic recycling operations have not been well studied, the toxic fumes resulting from the burning of plastics or plastic processing can cause respiratory illness. Regular exposure can subject workers and nearby residents to hundreds of toxic substances, including hydrochloric acid, sulfur dioxide, dioxins and heavy metals, the effects of which can include developmental disorders, endocrine disruption, and cancer.

Once the plastic is sorted by workers like Tham, others feed the scrap into grinders before putting it through densifiers that melt and condense the scrap so it can be molded into pellets.

(much more on the link)

.

Anybody who has looked at recycling knows it is a damned lie.

It is just a bunch of progressive virtue signalling.

The metals can be separated. But sorting the plastic either takes advanced AI and robotics - or someone in a third world country.

The real solution for the US is high temperature incineration of non-metallic garbage.

It can be used to generate power as part of a cogeneration facility.