nivek

As Above So Below

Magnetar

By Adam Kehoe

I got sick in what was supposed to be the closing chapter of my doctorate. At first, my spine and hip hurt. Later, my eyes started to get excruciatingly irritated and red. Then it became hard to walk and to stay awake. Stubborn, I only went to the doctor when I stopped being able to go to the bathroom without bleeding profusely.

My physician at the university told me he had younger patients than me with cancer. I needed diagnostics, urgently. The university health service sent me to a financial counselor afterwards to warn me what would happen next: my student insurance wasn't going to cover the testing.

The hospital lived up to its reputation. Someone with a face I don't recall asked me how much I could pay that day. I had the presence of mind to ask for lower and upper bounds on what I might expect for the final tally. She capably but absently walked me through what anesthesia might do to the bill.

I contemplated death a lot. I thought about the research I wasn't going to finish and the debt I would likely leave my family. At the time, I was still in love with someone I hadn't talked to in a long time. I was too scared to call her, so I'd imagine her face and think about the things we'd talk about when the time came.

Meanwhile my spine continued to speak to me. It told me every day: you're going to die, and it won't be pretty.

I called her once, but I didn't tell her why.

The hospital did its job in determining it wasn't cancer. It didn't do the other job, though: telling me what was actually wrong. Time stretched on, and the condition relented slightly – enough where I could fake functionality. The debt from the hospital mounted. Now I needed to sell my services as a technologist in order to continue to stay in grad school and finish my degree. Thus, I became a businessman.

Before long, the disease woke up again. This time I knew what the hospital would and wouldn't do. So, I scraped together money and paid for my own genetic testing and did the analysis myself.

It took me a week of reading and playing with genetic risk models. When I was done I made a crude application demonstrating the analysis so that others might benefit.

I learned that I have a middling-rare autoimmune condition that attacks the spine and the eyes. Another genetic risk factor exacerbates the problem and causes some unusual complications.

My spine hurt because it was gradually knitting together new bone. Unchecked, the disease would essentially create a completely fused mass. My eyes hurt because my immune system was destroying them; untreated I could potentially go blind. On average, it takes something like 11 years for someone to be properly diagnosed. It tends to strike young men, precisely when it hit me, in the late 20s.

I went back to the hospital, this time armed with a hypothesis. The diagnosis came quickly. New insurance battles began.

What followed, in the second awakening of my disease, was an education. My spine continued to speak to me. This time I knew it was lying when it told me it would kill me. It would merely cripple and deform me, instead.

The body and the mind, under sufficient stress, rebels from normal consciousness. One becomes acquainted with altered states – not in the sense of a recreational drug, or the fullness of prayer or meditation. The brain finds the more primal place; that old one we tend to forget as soon as we see it.

My experience of it was a little like Jung's concept of active imagination – I would try to gently steer a waking dream when my spine would not permit me to sleep.

There was a place I found myself returning to often. It was a star.

More accurately, it was a magnetar-pulsar. In the fugue, I hallucinated that my skin could somehow "hear" magnetism. I could "hear" its pulsation (likely my own heartbeat) as it rotated distantly in the void.

Usually I perceived the magnetar as a tiny but infinitely bright blue spark in the distance. A charismatic pinprick of light, really. As I approached it, the skin-sound synthesia strengthened until it became overwhelming.

I wanted to believe its magnetic radiation could become powerful enough to interfere with the normal firing of the neurons in my brain. In the waking dream, proximity to the star would erase the "me" that feels pain and leave me aware only of a raw pulsation and the perception of the essence of the color blue. Beholding this mad spinning thing, a screaming giant star, was liberation. I imagined dipping my head willingly in the radiation, entering the gateway into the first jhana.

Please don't judge me if the physics or biology are wrong; I apparently needed an image to survive and this was the best I had.

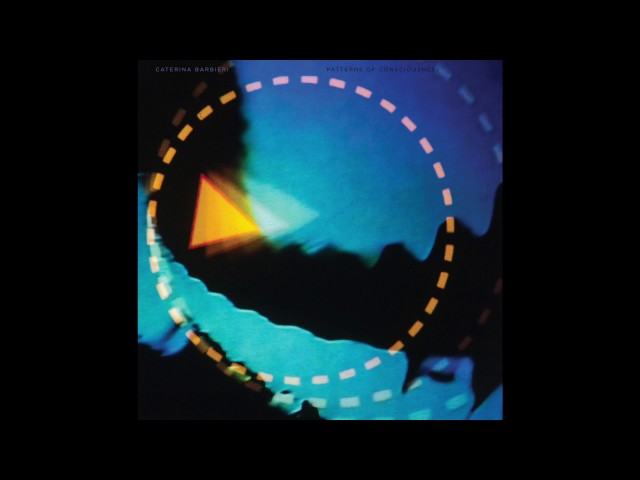

The best musical analog I can give you is this:

With good headphones, closed eyes and sufficient (i.e. slightly excessive) volume, it reminds me of being in the presence of the magnetar.

Needless to say, I survived the second awakening of the disease. Gradually the disease came under control. Some of the pain relented because only the active knitting of bone hurts. Once it is done, it is done. The right medication also helps.

In the meantime, what they say about things that don't kill you is true. I finished my doctorate. I grew my business. I more than paid my debts. I fell in love again.

I haven't seen the magnetar lately, but I know where it lives. It gave me an education in extremity, in what happens when the fight goes bad. You don't get to win every round. Fight on anyway.

.