pigfarmer

tall, thin, irritable

what a dick. but those fences will just give you a zap, I don't think anybody is going to be electrocuted

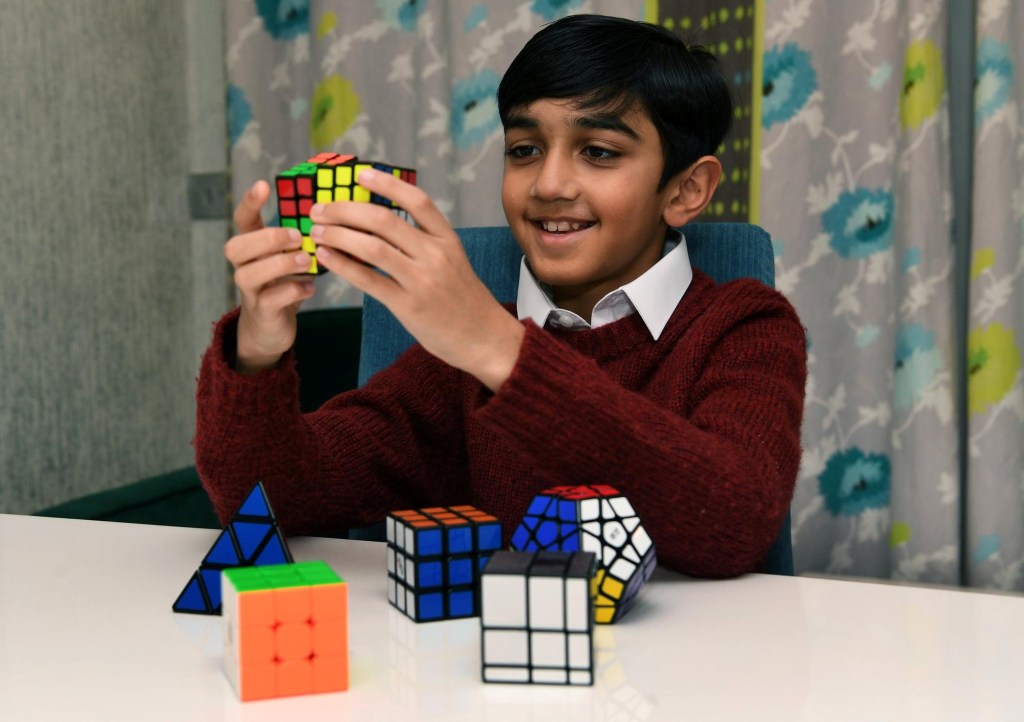

Yusuf’s dad jokingly says, “I still tell him that ‘your dad is still smarter than you.’ ”Yorkshire Post / SWNS

Yusuf’s dad jokingly says, “I still tell him that ‘your dad is still smarter than you.’ ”Yorkshire Post / SWNS

Yusuf Shah with brothers Zaki and Khalid, mother Sana and father Irfan.Yorkshire Post / SWNS

Yusuf Shah with brothers Zaki and Khalid, mother Sana and father Irfan.Yorkshire Post / SWNS

Oh, shell no! The WWI relic measured almost 8 inches long and more than 2 inches wide. Twitter / @acommonlawyer

Oh, shell no! The WWI relic measured almost 8 inches long and more than 2 inches wide. Twitter / @acommonlawyer “We had to manage the risk in a reactive framework,” a hospital spokesperson declared. “When in doubt, we took all the precautions.”Hôpital Sainte Musse

“We had to manage the risk in a reactive framework,” a hospital spokesperson declared. “When in doubt, we took all the precautions.”Hôpital Sainte Musse

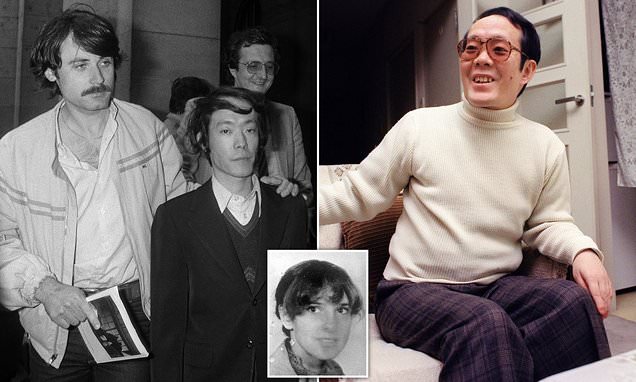

What's wrong with eating people?

You could soon be dining on lab-grown celebrity canapés and lightly-seasoned chunks of your loved ones. But is the world ready for synthesised cannibalism?

What if you could tuck into a juicy human burger that was guaranteed cruelty-free? No-one has to lose a shoulder for your Sunday roast; no-one gets their leg sawn off for your signature slow-cooked tagine. No-one even has to die these days. In the not-too-distant future, we could all be tucking into lab-grown meaty cubes of our favourite celebrities. Or eating a synthesised slab of newlyweds to mark the special day.

“In the West, this is a huge taboo,” says Dr. Bill Schutt, professor of biology, research associate in residence at the American Museum of Natural History and author of Eat Me: A Natural and Unnatural History of Cannibalism. “Especially the medicinal cannibalism that took place relatively recently in Europe. I think it was something that people probably weren’t particularly proud of, once they discovered that modern medicine had better solutions than eating body parts.”

In 2017, salves and tinctures made from people have fallen out of fashion with pharmacists. But what about the restaurant up the road? In 2013, scientists from the Netherlands proved that we can make animal meat in a lab from cell cultures into beef burgers (the first, which cost £215,000 to make was, apparently, “not that juicy”). But there is a difference between eating a cow and eating cow.

The latter is a massive win for cows. Cheek swab beats boltgun. For diners, too; once you factor in how much of your bill goes into breeding and sustaining livestock. There’s also no animal cruelty in a petri dish. With nothing more invasive than a cotton bud, anyone could eat as much beef as they like without harming a single cow.

Or as much human.

Dr. Koert Van Mensvoort, director of the Next Nature Network and fellow at the Eindhoven University of Technology, is the man behind what is probably the worst (but in a good way) cookbook you could ever hope to buy. The In Vitro Meat Cookbook contains recipes for over 40 dishes – none of which you can actually make. Yet. Each entry is illustrated, with an accompanying list of ingredients (all centred around lab-grown meat), a gleefully morbid description, and a five-star rating system of scientific feasibility. One star: we’re a long ways off. Five stars: Set the table! And use the good cutlery – we’re eating guests.

“I started writing the book because I was already in contact with some of the biotechnology companies that had been developing in vitro meat for years,” says Van Mensvoort. “And what was striking was that they were trying to make the same kinds of sausages and burgers that we already know. That sounded weird to me, like how people called the first cars horseless carriages. So I decided to step into their space and explore the creative design: what could be on our plates in the future because of this new technology?”

The In Vitro Meat Cookbook is really a cookbook in name only. It’s an art project, a conversation starter. There’s a recipe for knitted meat (“a festive centrepiece” to replace the Christmas turkey, four stars) and Dodo Nuggets (“The dodo has returned! To the dinner table”, also four stars).

Lab-grown human meat could be used to create cubes of celebrity meat.

.

Only towards the very end do things start turning shades of Soylent Green. Would sir or madame care for a Celebrity Cube? Cells swabbed from today’s hottest stars, grown into cubic canapes and speared on cocktail sticks. “Give European royalty a try before the next coronation,” the book suggests. Which would certainly change the atmosphere on The Mall. Celebrity Cubes might be feasible – if you can grow mutton, you can grow Miley – but even without a sacrificial lamb, any company hoping to sell lab-grown human flesh will, says Van Mensvoort, be selling to a market that is exclusive and esoteric in equal measure.

“In general, I think there will be huge reluctance against in vitro human meat,” he says. “It will be very, very niche. Maybe a very haute-cuisine restaurant will offer this once-in-a-lifetime, special experience for which you pay a lot of money. Or it could be a ritual: when you get married, you consume a piece of each other’s meat, just that once. I’m not promoting it, I just think it’s a fascinating conversation to have. The problems are much more social and cultural than technical or medical.”

But, providing the cell donor is informed and consenting, what is the problem? What is it about the image of a half-dozen friends, laughing and chatting in between mouthfuls of each other, that makes it so innately ghoulish? One plausible answer is that it’s ingrained that eating members of our own species is bad for us. Other animals – the list is longer and fluffier than you would hope – do it all the time. But at least in mammals, cannibalism is usually a product of extreme circumstance: food scarcity, environmental stressors, or one group fighting another and then eating infant usurpers.

(More on the link)

.