Dean

Adept Dabbler

Pentagon spokeswoman implies that the Navy

discarded longer versions of 3 UAP videos

By Douglas D. Johnson

@ddeanjohnson on Twitter

WASHINGTON (December 7, 2019) – According to a spokeswoman for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the Navy does not possess longer or better-definition versions of three widely circulated, hotly debated infrared (ATFLIR) videos of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP).

The Pentagon spokeswoman implied that longer video footage of the incidents may have been discarded as containing nothing useful “for future training.”

The three UAP videos under discussion were taken by Navy pilots during incidents in 2004 and 2015. The videos have been publicly referred to by the names FLIR1 (2004), Gimbal and GoFast (both 2015). Each publicly circulated video is short -- the longest barely over two minutes.

The new Pentagon claims came in an email to me dated December 6, 2019, from OSD public affairs spokeswoman Susan L. Gough, in response to five written questions. I originally submitted my questions to a Navy spokesman on October 2. The Navy spokesman forwarded them to Gough– because, he said, the OSD recently had “taken ownership” of all incoming UAP-related inquiries.

In a September statement to John Greenwald Jr. of TheBlackVault.com, Joseph Gradisher, spokesperson for the Director of Naval Intelligence (Vice Admiral Matthew J. Kohler), said, “The Navy considers the phenomena contained/depicted in those 3 videos as unidentified.”

The complete text of my five questions of October 2, with the complete December 6 responses from Susan Gough of OSD, appear at the bottom of this article, and are also attached as two .jpg images.

Two of the ATFLIR videos taken by Navy pilots were widely circulated beginning on December 16, 2017, in association with a prominent article in the New York Times, simultaneously released with commentary on the website of the To The Stars Academy.

One of these ATFLIR videos, labeled FLIR1, was taken by a Navy F/A-18 on November 14, 2004, during an extended series of encounters with UAPs by elements of a task force headed by the aircraft carrier Nimitz, off San Diego (events now referred to in aggregate as “the Nimitz encounter”).

The second video, “Gimbal,” was taken on January 21, 2015, off the Florida-Georgia coast, by a Navy pilot associated with the Roosevelt Carrier group – as was a video named “GoFast” that came into wide circulation via the To The Stars Academy in March 2018. FLIR1 is one minute, 16 seconds long, Gimbal 1:53, and GoFast 2:04.

There has been a great deal of debate regarding the routes and processes by which each of the three videos became public, but I won’t go into any of that here, as it is undisputed that all three are authentic ATFLIR images taken by Navy pilots on the dates described. I am far more interested in the assertions by multiple retired petty officers from the Princeton (a guided missile cruiser operating with the Nimitz), in various interviews, that they had seen a much longer and higher-definition version of the FLIR1 video, shortly after it was made.

A good narrative distillation of the recollections of five of these non-commissioned officers was published on November 12, 2019, in an article titled “The Witnesses,” by Tim McMillan, in Popular Mechanics

Navy UFO | UFO Sightings | The Truth About the Navy's UFOs

Gary Vooris, who in 2004 was a petty officer and system radar technician on the Princeton, told Popular Mechanics, “I definitely saw video that was roughly 8 to 10 minutes long and a lot more clear.”

Robert Powell, lead researcher on a team associated with the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies (SCU), was told similar things when he interviewed three of those same petty officers in 2018. For example, Petty Officer Third Class Jason Turner told Powell that “...the [public] video that you see is actually cut short ... It [the original] was quite a long video. The [public] video doesn’t show where this thing turned sideways and you can see it’s elongated and how it turned and went in a different direction that they couldn’t keep up with....The [public] one that we see is really really grainy. The one that we saw [on the ship], was not.”

Likewise, Senior Chief Petty Officer Kevin Day told Powell, “The video on the New York Times was probably about, I would say maybe, a half to a third as long as the original one that I received.”

Summaries of Powell’s interviews are found in Appendix E of A Forensic Analysis of Navy Carrier Strike Group Eleven’s Encounter with an Anomalous Aerial Vehicle, a very worthwhile 270-page forensic analysis of various aspects of the Nimitz encounter, issued by SCU earlier this year.

For further information on his interviews, contact Robert Powell at robertmaxpowell@gmail.com https://www.explorescu.org/post/nimitz_strike_group_2004

The first question in my October 2 submission was, “Does the Navy in fact possess, or have knowledge of possession within the Department of Defense, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the now-public UAP videos known as FLIR1, Gimbal, and GoFast?” OSD spokesperson Gough responded, “The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation.”

Gough’s next assertion I found particularly noteworthy – indeed, remarkable. She said: “Videos that are taken by the ATFLIR during training flights are not normally kept and maintained for record unless they had a significant learning aspect to them and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.”

In response to one of my other questions, Gough said, “The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified. The Navy has not authorized general release. Requests for these videos under Freedom of Information Act guidelines may be submitted by following the instructions at this site: Homepage | NAVAIR - FOIA

In response to my concluding question, in which I posed the proposition that no legitimate security or public policy purpose is served by denying civilian analysts access to longer or higher-definition versions of the three already-public videos, Gough replied in part: “The investigations into aerial incursions into our military training ranges are ongoing. Therefore, no public release of range incursion information is expected.”

Gough’s responses, puzzling as they are, were a long time coming. I originally submitted my questions by email on October 2, 2019, to Gradisher, the spokesman for Vice Admiral Kohler (who is both Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare, and Director of Naval Intelligence). According to previously published material, Naval Intelligence personnel had by that point conducted at least three classified UAP-related briefings for some members of key congressional committees (in December 2018, May 2019, and June 2019), with Kohler personally participating in at least the first of these.

On multiple occasions prior to my October 2 submission, and at least as recently as September 16, Gradisher had responded by email or by phone to questions from journalists and researchers (myself included), regarding Navy actions and policies pertaining to encounters between Navy pilots and “unidentified aerial phenomena.”

However, to my surprise, Gradisher responded to my October 2 questions with an email stating, “Department of Defense Public Affairs has taken the lead for responding to all media inquiries concerning UAPs. Sue Gough, cc’d, will be the one to respond to your latest set of questions.”

In a follow up phone conversation, Gradisher told me, in a matter-of-fact tone, that the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) “took ownership of the entire product,” on grounds that “this is getting so much play . . . we [OSD] need to take control of it.” The UAP issue affected “all services,” not only the Navy, Mr. Gradisher elaborated.

On October 17, having received no response to my five questions, I resubmitted them by email directly to Gough.

The next day, October 18, John Greenewald Jr. of TheBlackVault.com released a batch of UAP-related, military-originated materials he had obtained through the Freedom of Information Act process, including a September 20 email with the subject line “FW: UFOs/The New York Times,” sent by Gough to Gradisher and to an Air Force public affairs officer. In this email, Gough said, “Navy has requested that OSD take the lead from now on for these [UAP] queries, so please continue to work any USAF-specific responses through me.”

On December 4, I called Gradisher and asked him about the apparent discrepancy regarding whether it was OSD or the Navy that had initiated OSD’s takeover of all public responses to UAP-related inquiries. He declined to comment, except to reiterate that OSD is now “the sole point of contact” for UAP-related inquiries from the media and public. However, he kindly volunteered to again forward my five questions to Ms. Gough, for which I thanked him. The email from Gough arrived two days later.

(In her December 6 email to me, Gough attributed the long delay in responding to my questions as due to “some Outlook issues...your emails were inadvertently sent to another folder.”)

Returning to the substance of Gough’s responses, my reading is that Gough implicitly acknowledges that longer video recordings of the Navy pilot incidents initially existed-- yet she asserts that only the short videos were retained, because only those brief sections contained “a significant learning aspect and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.”

(At no point did Gough address the question of whether the existing "source videos" are of lower clarity/definition than the videos originally recorded by the Raytheon devices used by the Navy planes.)

I expect that Gough’s suggestion that additional video footage of the object recorded during the Nimitz encounters was discarded as devoid of “a significant learning aspect" -- when the Navy says the object depicted is still “unidentified” 15 years later -- will be greeted with considerable skepticism by many who have studied the details of the Nimitz encounter, to say nothing of the broader history of military encounters with UAPs. I anticipate that analysts of the 2015 videos made by a Roosevelt-based pilot or pilots will also consider Gough’s assertions to raise significant questions.

Finally: to my reading, Gough did not explicitly declare that OSD has no knowledge that any entity outside the Navy received or currently retains possession of longer and/or higher-definition videos of the 2004 or 2015 incidents – video files that may have been made from the original ATFLIR video files, prior to whatever unspecified editing process produced what Gough now calls the “source videos.” Surely, however, Gough’s wording seems carefully crafted to leave the impression that no such longer/clearer videos have survived. Therefore, if such additional video imagery is someday found to exist -- perhaps under the control of some component of the Defense Department other than the Navy, or some organ of the non-military intelligence community – then the December 6 responses that I received would be judged to have been seriously misleading.

Douglas D. Johnson

Research Affiliate, Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies

@ddeanjohnson on Twitter

***

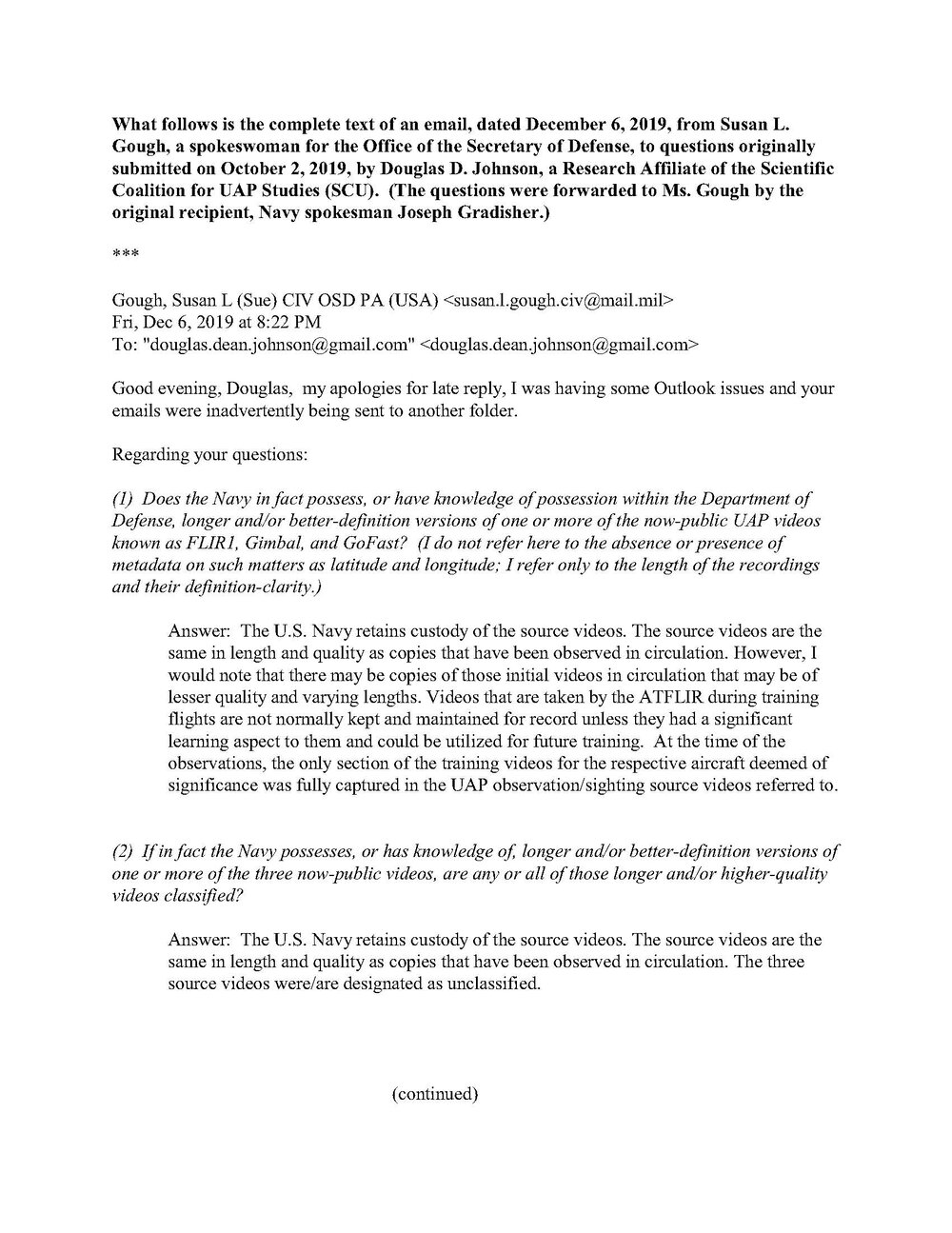

What follows is the complete text of an email, dated December 6, 2019, from Susan L. Gough, a spokeswoman for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), to questions originally submitted on October 2, 2019, by Douglas D. Johnson, a Research Affiliate of the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies (SCU). The questions were forwarded to Ms. Gough by the original recipient, Joseph Gradisher, spokesman for the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare. The Gough email is also reproduced in two attached .jpg files.

***

Gough, Susan L (Sue) CIV OSD PA (USA) <susan.l.gough.civ@mail.mil>

Fri, Dec 6, 2019 at 8:22 PM

To: "douglas.dean.johnson@gmail.com" <douglas.dean.johnson@gmail.com>

Good evening, Douglas, my apologies for late reply, I was having some Outlook issues and your emails were inadvertently being sent to another folder. Regarding your questions:

(1) Does the Navy in fact possess, or have knowledge of possession within the Department of Defense, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the now-public UAP videos known as FLIR1, Gimbal, and GoFast? (I do not refer here to the absence or presence of metadata on such matters as latitude and longitude; I refer only to the length of the recordings and their definition-clarity.)

Answer: The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation. However, I would note that there may be copies of those initial videos in circulation that may be of lesser quality and varying lengths. Videos that are taken by the ATFLIR during training flights are not normally kept and maintained for record unless they had a significant learning aspect to them and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.

(2) If in fact the Navy possesses, or has knowledge of, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the three now-public videos, are any or all of those longer and/or higher-quality videos classified?

Answer: The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation. The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified.

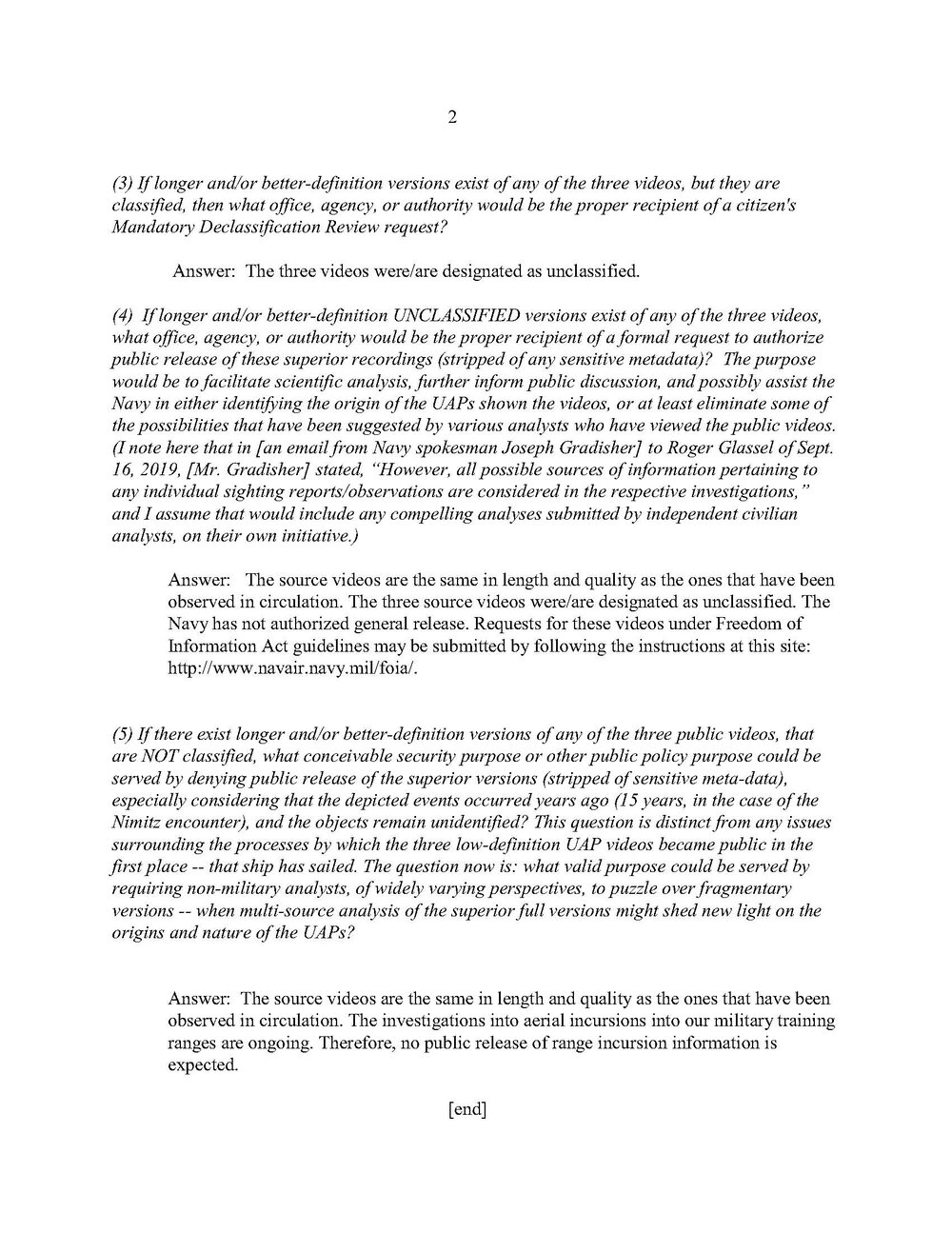

(3) If longer and/or better-definition versions exist of any of the three videos, but they are classified, then what office, agency, or authority would be the proper recipient of a citizen's Mandatory Declassification Review request?

Answer: The three videos were/are designated as unclassified.

(4) If longer and/or better-definition UNCLASSIFIED versions exist of any of the three videos, what office, agency, or authority would be the proper recipient of a formal request to authorize public release of these superior recordings (stripped of any sensitive metadata)? The purpose would be to facilitate scientific analysis, further inform public discussion, and possibly assist the Navy in either identifying the origin of the UAPs shown the videos, or at least eliminate some of the possibilities that have been suggested by various analysts who have viewed the public videos. (I note here that in [an email from Navy spokesman Joseph Gradisher] to Roger Glassel of Sept. 16, 2019, [Mr. Gradisher] stated, “However, all possible sources of information pertaining to any individual sighting reports/observations are considered in the respective investigations,” and I assume that would include any compelling analyses submitted by independent civilian analysts, on their own initiative.)

Answer: The source videos are the same in length and quality as the ones that have been observed in circulation. The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified. The Navy has not authorized general release. Requests for these videos under Freedom of Information Act guidelines may be submitted by following the instructions at this site: Homepage | NAVAIR - FOIA.

(5) If there exist longer and/or better-definition versions of any of the three public videos, that are NOT classified, what conceivable security purpose or other public policy purpose could be served by denying public release of the superior versions (stripped of sensitive meta-data), especially considering that the depicted events occurred years ago (15 years, in the case of the Nimitz encounter), and the objects remain unidentified? This question is distinct from any issues surrounding the processes by which the three low-definition UAP videos became public in the first place -- that ship has sailed. The question now is: what valid purpose could be served by requiring non-military analysts, of widely varying perspectives, to puzzle over fragmentary versions -- when multi-source analysis of the superior full versions might shed new light on the origins and nature of the UAPs?

Answer: The source videos are the same in length and quality as the ones that have been observed in circulation. The investigations into aerial incursions into our military training ranges are ongoing. Therefore, no public release of range incursion information is expected.

[end]

discarded longer versions of 3 UAP videos

By Douglas D. Johnson

@ddeanjohnson on Twitter

WASHINGTON (December 7, 2019) – According to a spokeswoman for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the Navy does not possess longer or better-definition versions of three widely circulated, hotly debated infrared (ATFLIR) videos of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP).

The Pentagon spokeswoman implied that longer video footage of the incidents may have been discarded as containing nothing useful “for future training.”

The three UAP videos under discussion were taken by Navy pilots during incidents in 2004 and 2015. The videos have been publicly referred to by the names FLIR1 (2004), Gimbal and GoFast (both 2015). Each publicly circulated video is short -- the longest barely over two minutes.

The new Pentagon claims came in an email to me dated December 6, 2019, from OSD public affairs spokeswoman Susan L. Gough, in response to five written questions. I originally submitted my questions to a Navy spokesman on October 2. The Navy spokesman forwarded them to Gough– because, he said, the OSD recently had “taken ownership” of all incoming UAP-related inquiries.

In a September statement to John Greenwald Jr. of TheBlackVault.com, Joseph Gradisher, spokesperson for the Director of Naval Intelligence (Vice Admiral Matthew J. Kohler), said, “The Navy considers the phenomena contained/depicted in those 3 videos as unidentified.”

The complete text of my five questions of October 2, with the complete December 6 responses from Susan Gough of OSD, appear at the bottom of this article, and are also attached as two .jpg images.

Two of the ATFLIR videos taken by Navy pilots were widely circulated beginning on December 16, 2017, in association with a prominent article in the New York Times, simultaneously released with commentary on the website of the To The Stars Academy.

One of these ATFLIR videos, labeled FLIR1, was taken by a Navy F/A-18 on November 14, 2004, during an extended series of encounters with UAPs by elements of a task force headed by the aircraft carrier Nimitz, off San Diego (events now referred to in aggregate as “the Nimitz encounter”).

The second video, “Gimbal,” was taken on January 21, 2015, off the Florida-Georgia coast, by a Navy pilot associated with the Roosevelt Carrier group – as was a video named “GoFast” that came into wide circulation via the To The Stars Academy in March 2018. FLIR1 is one minute, 16 seconds long, Gimbal 1:53, and GoFast 2:04.

There has been a great deal of debate regarding the routes and processes by which each of the three videos became public, but I won’t go into any of that here, as it is undisputed that all three are authentic ATFLIR images taken by Navy pilots on the dates described. I am far more interested in the assertions by multiple retired petty officers from the Princeton (a guided missile cruiser operating with the Nimitz), in various interviews, that they had seen a much longer and higher-definition version of the FLIR1 video, shortly after it was made.

A good narrative distillation of the recollections of five of these non-commissioned officers was published on November 12, 2019, in an article titled “The Witnesses,” by Tim McMillan, in Popular Mechanics

Navy UFO | UFO Sightings | The Truth About the Navy's UFOs

Gary Vooris, who in 2004 was a petty officer and system radar technician on the Princeton, told Popular Mechanics, “I definitely saw video that was roughly 8 to 10 minutes long and a lot more clear.”

Robert Powell, lead researcher on a team associated with the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies (SCU), was told similar things when he interviewed three of those same petty officers in 2018. For example, Petty Officer Third Class Jason Turner told Powell that “...the [public] video that you see is actually cut short ... It [the original] was quite a long video. The [public] video doesn’t show where this thing turned sideways and you can see it’s elongated and how it turned and went in a different direction that they couldn’t keep up with....The [public] one that we see is really really grainy. The one that we saw [on the ship], was not.”

Likewise, Senior Chief Petty Officer Kevin Day told Powell, “The video on the New York Times was probably about, I would say maybe, a half to a third as long as the original one that I received.”

Summaries of Powell’s interviews are found in Appendix E of A Forensic Analysis of Navy Carrier Strike Group Eleven’s Encounter with an Anomalous Aerial Vehicle, a very worthwhile 270-page forensic analysis of various aspects of the Nimitz encounter, issued by SCU earlier this year.

For further information on his interviews, contact Robert Powell at robertmaxpowell@gmail.com https://www.explorescu.org/post/nimitz_strike_group_2004

The first question in my October 2 submission was, “Does the Navy in fact possess, or have knowledge of possession within the Department of Defense, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the now-public UAP videos known as FLIR1, Gimbal, and GoFast?” OSD spokesperson Gough responded, “The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation.”

Gough’s next assertion I found particularly noteworthy – indeed, remarkable. She said: “Videos that are taken by the ATFLIR during training flights are not normally kept and maintained for record unless they had a significant learning aspect to them and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.”

In response to one of my other questions, Gough said, “The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified. The Navy has not authorized general release. Requests for these videos under Freedom of Information Act guidelines may be submitted by following the instructions at this site: Homepage | NAVAIR - FOIA

In response to my concluding question, in which I posed the proposition that no legitimate security or public policy purpose is served by denying civilian analysts access to longer or higher-definition versions of the three already-public videos, Gough replied in part: “The investigations into aerial incursions into our military training ranges are ongoing. Therefore, no public release of range incursion information is expected.”

Gough’s responses, puzzling as they are, were a long time coming. I originally submitted my questions by email on October 2, 2019, to Gradisher, the spokesman for Vice Admiral Kohler (who is both Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare, and Director of Naval Intelligence). According to previously published material, Naval Intelligence personnel had by that point conducted at least three classified UAP-related briefings for some members of key congressional committees (in December 2018, May 2019, and June 2019), with Kohler personally participating in at least the first of these.

On multiple occasions prior to my October 2 submission, and at least as recently as September 16, Gradisher had responded by email or by phone to questions from journalists and researchers (myself included), regarding Navy actions and policies pertaining to encounters between Navy pilots and “unidentified aerial phenomena.”

However, to my surprise, Gradisher responded to my October 2 questions with an email stating, “Department of Defense Public Affairs has taken the lead for responding to all media inquiries concerning UAPs. Sue Gough, cc’d, will be the one to respond to your latest set of questions.”

In a follow up phone conversation, Gradisher told me, in a matter-of-fact tone, that the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) “took ownership of the entire product,” on grounds that “this is getting so much play . . . we [OSD] need to take control of it.” The UAP issue affected “all services,” not only the Navy, Mr. Gradisher elaborated.

On October 17, having received no response to my five questions, I resubmitted them by email directly to Gough.

The next day, October 18, John Greenewald Jr. of TheBlackVault.com released a batch of UAP-related, military-originated materials he had obtained through the Freedom of Information Act process, including a September 20 email with the subject line “FW: UFOs/The New York Times,” sent by Gough to Gradisher and to an Air Force public affairs officer. In this email, Gough said, “Navy has requested that OSD take the lead from now on for these [UAP] queries, so please continue to work any USAF-specific responses through me.”

On December 4, I called Gradisher and asked him about the apparent discrepancy regarding whether it was OSD or the Navy that had initiated OSD’s takeover of all public responses to UAP-related inquiries. He declined to comment, except to reiterate that OSD is now “the sole point of contact” for UAP-related inquiries from the media and public. However, he kindly volunteered to again forward my five questions to Ms. Gough, for which I thanked him. The email from Gough arrived two days later.

(In her December 6 email to me, Gough attributed the long delay in responding to my questions as due to “some Outlook issues...your emails were inadvertently sent to another folder.”)

Returning to the substance of Gough’s responses, my reading is that Gough implicitly acknowledges that longer video recordings of the Navy pilot incidents initially existed-- yet she asserts that only the short videos were retained, because only those brief sections contained “a significant learning aspect and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.”

(At no point did Gough address the question of whether the existing "source videos" are of lower clarity/definition than the videos originally recorded by the Raytheon devices used by the Navy planes.)

I expect that Gough’s suggestion that additional video footage of the object recorded during the Nimitz encounters was discarded as devoid of “a significant learning aspect" -- when the Navy says the object depicted is still “unidentified” 15 years later -- will be greeted with considerable skepticism by many who have studied the details of the Nimitz encounter, to say nothing of the broader history of military encounters with UAPs. I anticipate that analysts of the 2015 videos made by a Roosevelt-based pilot or pilots will also consider Gough’s assertions to raise significant questions.

Finally: to my reading, Gough did not explicitly declare that OSD has no knowledge that any entity outside the Navy received or currently retains possession of longer and/or higher-definition videos of the 2004 or 2015 incidents – video files that may have been made from the original ATFLIR video files, prior to whatever unspecified editing process produced what Gough now calls the “source videos.” Surely, however, Gough’s wording seems carefully crafted to leave the impression that no such longer/clearer videos have survived. Therefore, if such additional video imagery is someday found to exist -- perhaps under the control of some component of the Defense Department other than the Navy, or some organ of the non-military intelligence community – then the December 6 responses that I received would be judged to have been seriously misleading.

Douglas D. Johnson

Research Affiliate, Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies

@ddeanjohnson on Twitter

***

What follows is the complete text of an email, dated December 6, 2019, from Susan L. Gough, a spokeswoman for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), to questions originally submitted on October 2, 2019, by Douglas D. Johnson, a Research Affiliate of the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies (SCU). The questions were forwarded to Ms. Gough by the original recipient, Joseph Gradisher, spokesman for the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare. The Gough email is also reproduced in two attached .jpg files.

***

Gough, Susan L (Sue) CIV OSD PA (USA) <susan.l.gough.civ@mail.mil>

Fri, Dec 6, 2019 at 8:22 PM

To: "douglas.dean.johnson@gmail.com" <douglas.dean.johnson@gmail.com>

Good evening, Douglas, my apologies for late reply, I was having some Outlook issues and your emails were inadvertently being sent to another folder. Regarding your questions:

(1) Does the Navy in fact possess, or have knowledge of possession within the Department of Defense, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the now-public UAP videos known as FLIR1, Gimbal, and GoFast? (I do not refer here to the absence or presence of metadata on such matters as latitude and longitude; I refer only to the length of the recordings and their definition-clarity.)

Answer: The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation. However, I would note that there may be copies of those initial videos in circulation that may be of lesser quality and varying lengths. Videos that are taken by the ATFLIR during training flights are not normally kept and maintained for record unless they had a significant learning aspect to them and could be utilized for future training. At the time of the observations, the only section of the training videos for the respective aircraft deemed of significance was fully captured in the UAP observation/sighting source videos referred to.

(2) If in fact the Navy possesses, or has knowledge of, longer and/or better-definition versions of one or more of the three now-public videos, are any or all of those longer and/or higher-quality videos classified?

Answer: The U.S. Navy retains custody of the source videos. The source videos are the same in length and quality as copies that have been observed in circulation. The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified.

(3) If longer and/or better-definition versions exist of any of the three videos, but they are classified, then what office, agency, or authority would be the proper recipient of a citizen's Mandatory Declassification Review request?

Answer: The three videos were/are designated as unclassified.

Answer: The source videos are the same in length and quality as the ones that have been observed in circulation. The three source videos were/are designated as unclassified. The Navy has not authorized general release. Requests for these videos under Freedom of Information Act guidelines may be submitted by following the instructions at this site: Homepage | NAVAIR - FOIA.

(5) If there exist longer and/or better-definition versions of any of the three public videos, that are NOT classified, what conceivable security purpose or other public policy purpose could be served by denying public release of the superior versions (stripped of sensitive meta-data), especially considering that the depicted events occurred years ago (15 years, in the case of the Nimitz encounter), and the objects remain unidentified? This question is distinct from any issues surrounding the processes by which the three low-definition UAP videos became public in the first place -- that ship has sailed. The question now is: what valid purpose could be served by requiring non-military analysts, of widely varying perspectives, to puzzle over fragmentary versions -- when multi-source analysis of the superior full versions might shed new light on the origins and nature of the UAPs?

Answer: The source videos are the same in length and quality as the ones that have been observed in circulation. The investigations into aerial incursions into our military training ranges are ongoing. Therefore, no public release of range incursion information is expected.

Attachments

Last edited: